|

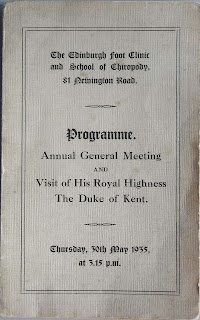

| Front cover of programme |

This week we have received a charming accession which will be added to our Edinburgh Foot Clinic and School of Chiropody collection. It consists of the programme for the Clinic’s AGM and the visit of HRH, the Duke of Kent on 30th May 1935. Enclosed with the programme, which measures approximately 9cm by 5cm, was a photograph of the Duke meeting nurses at the clinic.

The Edinburgh Foot Clinic was opened in 1924 by Miss Catherine Norrie and her sister Mrs Margaret Swanson to treat ‘minor foot ailments of the working class’. Situated at 1a Hill Place, it was open for two or three half days each week and was staffed by volunteers. Patients paid a minimum charge of 1/- and, if possible, an extra donation. In 1928 the Clinic moved to 81 Newington Road, due to increased demand for its services and the consequent need for larger premises. During World War II mobile chiropody units were set up for the Services. By 1948 the Clinic was open on all week days and on Wednesday evenings. It still catered mainly for working class patients. Most applied for treatment directly to the Clinic, although some were referred by their GPs. The National Health Service took over the running of the Clinic in 1948. You can view the full catalogue on our website: Edinburgh Foot Clinic Catalogue.

|

| HRH the Duke of Kent meets nurses |

.jpg)